"I think I’m going to Die!

I think I’m going to Die!!!"

This phrase keeps repeating over and over again in my head as I struggle to take another lunge-like step up the steep and jagged Nangkartshang Peak, also known as Nangkart Tshang. There’s not even a trail on this black mountain! Although it is technically a sub-peak of a higher ridge, it turns into a razor sharp knife edge and requires technical climbing gear after the false summit.

Not only do I feel like I’m going to fall, as my feet make quick and slippery decisions on where to step on or between rocks, but my heart is pounding faster than I can count. It feels like it’s going to explode!

Not only do I feel like I’m going to fall, as my feet make quick and slippery decisions on where to step on or between rocks, but my heart is pounding faster than I can count. It feels like it’s going to explode!

Dingboche village with black mountain, Nangkartshang Peak, covered by the clouds

Today, March 15, 2017, was supposed to just be an “acclimation day” on the sixth day of the Everest Base Camp Trek with Mosaic Adventures. Typically, when we humans travel to higher altitudes (over 6,500 feet), our bodies take about two weeks to complete the acclimation process. Starting the trek in Lukla, Nepal, at around 8,500 feet, we made our way slowly up to this village at 14,469 feet, in four days.

However, this morning, our group ascended a steep hill for about two hours, then returned back down to camp, our teahouse accommodation in Dingboche. My roommate, Zoe, and I decided that we had nothing to do in this very small village, so we might as well just climb a little higher.

However, this morning, our group ascended a steep hill for about two hours, then returned back down to camp, our teahouse accommodation in Dingboche. My roommate, Zoe, and I decided that we had nothing to do in this very small village, so we might as well just climb a little higher.

The point where Zoe and I decided to climb a little higher.

Photo Credit: Mandi Thorpe

Photo Credit: Mandi Thorpe

However, after about 15 minutes of further ascent, a windchill of minus 5 degrees Farenheit, swallows us into a blizzard!

There’s got to be another word for this kind of cold!

Freezing doesn’t work either.

This is 37 degrees chillier than that!

My scarf around my chin is now frozen from my breath. It’s no longer doing it’s job of protecting my face!

There’s got to be another word for this kind of cold!

Freezing doesn’t work either.

This is 37 degrees chillier than that!

My scarf around my chin is now frozen from my breath. It’s no longer doing it’s job of protecting my face!

Our guide, disappeared into the blizzard up ahead. I can’t even see farther than 20 feet in front of me! I look back at Zoe.

“Should we keep going?” I yell.

“A little further” She utters.

“Do you want to lead?”

No, just keep going.” Zoe urges.

“Should we keep going?” I yell.

“A little further” She utters.

“Do you want to lead?”

No, just keep going.” Zoe urges.

We were caught in a paradox. The faster you move, the warmer your body feels. Also, the faster you move, the faster your heart beats, and it can only beat so fast.

Our heart is an adaptable organ and its function is to provide our organs and tissues with oxygenated blood and return deoxygenated blood to our lungs to become oxygenated again. In 32 degrees Farenheit at sea level, there is approximately 21% effective oxygen in the air. However, where we are now, on this cold mountain above 16000 feet, there is less than 11%. Therefore, our hearts need to beat twice as fast because of the density of oxygen present in the surrounding air. At 15,000 feet, our heart rate increases 50% higher than its regular sea level rate and increases even more with dropping temperatures. When we complete the acclimation process (after two weeks in high altitudes), our resting heart rate decreases and returns back to the same heart rate values that we had at our original altitude (i.e. home or where we were adjusted to before this experience).

This struggle to stay alive on Nangkartshang Peak is real and I’m not exaggerating. Many other adventurers experience the same difficulty in these conditions. The Walking Englishman claims, “It is a brutal ascent one that would have been hard enough in our beautiful Lake District but here with very little oxygen is proving to be very tough indeed. Only six of the sixteen of us make it to the summit and I do not mind saying with 400ft to go I stopped every thirty or forty paces, this is murder especially with this bloody cold. It is so hard, so hard, with no oxygen. Just trying to keep my heart inside my body is hard, its pounding within my chest enough to feel with my heavily gloved hand. I drink more water wishing I had taken Diamox but it is all too late by now and would do me no good at all.”

As I pause, gasping for a few deep breaths, I remember the mantra, "Bistari, bistari", that the Himalayan guides chant throughout each day of the trek. This means "slowly, slowly" to calm our hearts and our breath.

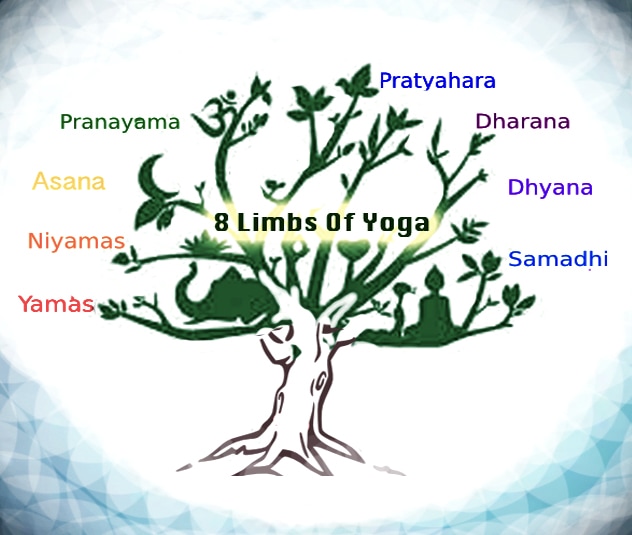

The word Prāṇāyāma, what we yogis know as breathing exercises (from the 4th Limb of Pantajali’s Path to Enlightenment), derives from the Sanskrit words prāna and ayāma, translating as "life force" and "expansion." Pranayama is considered to be one of the highest forms of purification and self-discipline for the mind and the body.

Our heart is an adaptable organ and its function is to provide our organs and tissues with oxygenated blood and return deoxygenated blood to our lungs to become oxygenated again. In 32 degrees Farenheit at sea level, there is approximately 21% effective oxygen in the air. However, where we are now, on this cold mountain above 16000 feet, there is less than 11%. Therefore, our hearts need to beat twice as fast because of the density of oxygen present in the surrounding air. At 15,000 feet, our heart rate increases 50% higher than its regular sea level rate and increases even more with dropping temperatures. When we complete the acclimation process (after two weeks in high altitudes), our resting heart rate decreases and returns back to the same heart rate values that we had at our original altitude (i.e. home or where we were adjusted to before this experience).

This struggle to stay alive on Nangkartshang Peak is real and I’m not exaggerating. Many other adventurers experience the same difficulty in these conditions. The Walking Englishman claims, “It is a brutal ascent one that would have been hard enough in our beautiful Lake District but here with very little oxygen is proving to be very tough indeed. Only six of the sixteen of us make it to the summit and I do not mind saying with 400ft to go I stopped every thirty or forty paces, this is murder especially with this bloody cold. It is so hard, so hard, with no oxygen. Just trying to keep my heart inside my body is hard, its pounding within my chest enough to feel with my heavily gloved hand. I drink more water wishing I had taken Diamox but it is all too late by now and would do me no good at all.”

As I pause, gasping for a few deep breaths, I remember the mantra, "Bistari, bistari", that the Himalayan guides chant throughout each day of the trek. This means "slowly, slowly" to calm our hearts and our breath.

The word Prāṇāyāma, what we yogis know as breathing exercises (from the 4th Limb of Pantajali’s Path to Enlightenment), derives from the Sanskrit words prāna and ayāma, translating as "life force" and "expansion." Pranayama is considered to be one of the highest forms of purification and self-discipline for the mind and the body.

Prana can be understood by us westerners with the word Oxygen. Prana enters the body through the breath and is sent to every cell through the circulatory system. Prāṇa ultimately relates to the beating of the heart and breathing. Without it, we will die within minutes. In fact, some humans (currently dozens to hundreds worldwide) can actually live on Prana alone. This lifestyle called Living on Prana, or Breathariansim has been documented for thousands of years. This is described in the Yoga Sutras as Pada 111.30: liberation from hunger and thirst (As a disclaimer, there have been multiple reports of deaths occurring as a result of people engaging in this practice, and there is much more involved with your intentions and prana practice, than simply refraining from eating or drinking)

Process of transition to Living on Prana

Photo Credit: Collective Evolution

Photo Credit: Collective Evolution

The word Air comes from the Latin word spirare. Its fundamental importance to life can be seen in words such as inspire, perspire and spirit.

Therefore our spirit (breath or life force) has the power to inspire us to perspire, or go a little further than our comfort zone!

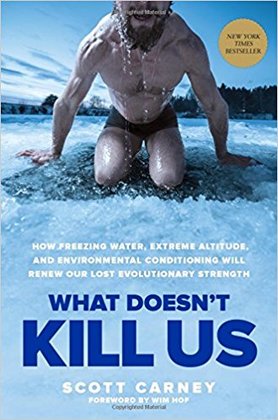

Scott Carney’s book, What Doesn't Kill Us explores the true connection between the mind and the body and reveals the science that allows us to push past our apparent limitations. Our ancestors crossed deserts, mountains, and oceans in a variety of altitudes and weather conditions. Those achievements of strength now seem impossible in an age where we take comfort for granted. Carney explains further, “much of the developing world—no longer suffers from diseases of deficiency. Instead we get the diseases of excess…We’re being eaten by cancer, by diabetes, and our own immune systems. There’s no wolf to run from, so our bodies eat themselves.” Carney encourages that through breath control and cold-training we can dramatically enhance energy levels, improve circulation, reduce stress, boost the immune system, strengthen the body and successfully combat many diseases.

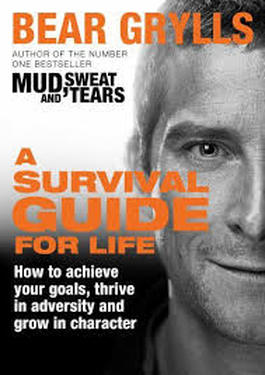

Similarily the survival expert and one of my favorite heroes, Bear Grylls, teaches in A Survival Guide for Life, “whenever you do something beyond your ‘comfort zone’ and realize you are still standing, the more you will believe that the impossible is actually possible. And on the road to success, belief is everything...we all have much further to push ourselves than we might initially imagine. Inside us all, just waiting to be tested, is a better, bolder, braver version of who we think we are.”

At the trekker's peak of black mountain we were overcome with lightness and joy, knowing that we were now stronger, braver, and more in touch with our spirit!